Rhino Research: Dung Testing to Support Translocation

Members of the Chester Zoo science team have joined Kenyan scientists to monitor endangered rhino populations by testing their dung.

Katie Edwards, Lead Conservation Scientist, recently travelled out with Rebecca Mogey, Laboratory Coordinator, to Kenya Wildlife Service Headquarters in Nairobi, as part of a project aiming to prevent the extinction of the eastern black rhino.

Chester Zoo has developed a conservation physiology lab on the zoo grounds which, since opening in 2007, has supported the breeding of 12 black rhino calves at the Zoo. Now the scientists behind this success are lending their technology and expertise to help to improve breeding rates and rhino relocations in Kenya.

They have joined Cedric Khayale, PhD candidate and Senior Research Scientist at the Wildlife Research and Training Institute, to undertake the first on-site testing of hundreds of faecal samples collected from critically endangered eastern black rhinos across Kenya, only around 1,000 of which live in the wild.

“We’ve learned a lot about eastern black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis michaeli) physiology ex situ at Chester Zoo, and we have been working to put that into practice with wild populations. Now we’re at the stage where we can start to analyse the faecal samples that have been collected by Cedric and his team over the last few years.”

Katie Edwards

Chester Zoo is involved in international efforts to monitor and protect black rhino populations, including supporting Big Life Foundation and Kenya Wildlife Service to set up camera traps and train rangers to prevent poaching in Chyulu Hills in southeast Kenya.

The newly operational lab has processed 390 samples collected by Cedric from several reserves, including Loisaba, a 58,000-acre wildlife conservancy located in Laikipia, Northern Kenya.

“The current work will support rhino translocation and meta population management efforts. Rhino populations in certain areas are breeding well, but those rates will naturally drop as an area reaches capacity. It is crucial rhinos are introduced to new suitable habitats so their numbers can expand, and this part of the endocrinology project will give us a clearer idea of how to do that safely and successfully. A new population has been established in Loisaba, and I have taken faecal samples before, during and after their translocation.

Cedric Khayale

Rhinos must be anesthetised before they are translocated to a new area. Physiological responses to the process can vary greatly; some rhinos enter a deeply sedated state, while others do not.

By measuring the stress hormone levels of the 21 Loisaba rhinos before, during and after this process, the scientists and conservationists can monitor how a rhino has responded to both the anaesthetic and the journey, and how well they have adapted to their new environment.

Cedric, Katie and Becky hope this data can also be used to predict outcomes for rhinos involved in future translocations, reducing stress, and making sure they are comfortable in their new homes.

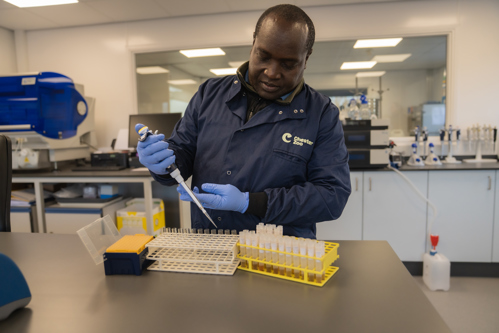

The key equipment installed at the lab includes a plate reader provided by Aspect Scientific, which will allow scientists to carry out multiple assays (investigative procedures) on prepared specimens of rhino faeces.

Transporting the reagents, chemical mixtures designed to change colour when exposed to the tested hormones, was perhaps the most delicate aspect of this stage of the project, as they must be kept at strictly controlled temperatures. Katie and Becky travelled to Kenya not just to carry out the work, but also to safely escort these testing components to the lab.

Katie said: “Our eventual goal is to build capacity so scientists like Cedric can work in the long term. We want conservation physiology as a scientific field to be accessible and affordable for Kenyan conservation scientists working on different projects. The techniques we are using with the Loisaba rhinos in Kenya have been applied to over 100 different species at Chester Zoo. These methods are certainly applicable to other endangered species."

Katie continued, “The idea is to have a pop-up lab, so the equipment and skills can be deployed where they are needed. We also want to train up people to use the lab. The most important thing to the future of this work is relationship building.

“In terms of this project, Cedric has collected the samples, we’ve done the homework and know what we need to measure. It’s now a case of getting the results.”

Cedric’s project is supported by Chester Zoo, Wildlife Research and Training Institute, Kenyan Wildlife Service, Manchester Metropolitan University, WWF-Kenya/UK and the Zoological Society of London.

To find out more about science at Chester Zoo, click here.